From: Richard Thomas [mailto:richardathomas@optonline.net]

Sent: Saturday, June 10, 2017 1:44 AM

This Sunday is the first Sunday after Pentecost. It’s also the last day of Sunday School until Fall and the day of the church picnic.

Trinitarianism

For the western liturgical denominations (Roman Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican, Methodist, and Presbyterian), this Sunday is also Trinity Sunday.

Trinitarianism took centuries to develop and disputes over the concept reached a peak early in the fourth century. Even though the word “Trinity” never appears in the Bible, and the number always associated with God in the Bible is the number “one,” (not “three”), the followers of Jesus needed some way of expressing his uniquely divine nature and the relationship between Christ and God.

Arius and his followers (the Arians) argued that Jesus was a created being, the son of God, and was thus subordinate to the Father. Athanasius and his party said that the Son was also fully God, co-equal and co-eternal with the Father.

About this time Emperor Constantine adopted Christianity and made it the Roman Empire’s official religion. He didn’t like the idea of there being no agreement on such an important matter and called for a general council which met at Nicaea in 325 A.D. The Emperor himself attended and even sometimes presided. Athanasius won the day, and thus we have the Nicene Creed. Arius and those bishops who had sided with him were excommunicated.

That still left the Holy Spirit. In the preceding century, most Christians held that the Holy Spirit was a divine power, but as time passed, more came to the conclusion that the Holy Spirit was a divine person. Another council had to be held, this time at Constantinople in 381 A.D. It was decided that the Holy Spirit was indeed a divine person, distinct from the person of the Father and the person of the Son.

Then they thought they had perhaps gone too far is stressing the wholly divine nature of Jesus, and held another council at Ephesus in 431 A.D, to declare that Jesus, though being divine, was also human. Also, in addition to reaffirming the humanness of Jesus, they noted that Mary was not just the mother of a special human baby, the baby Jesus, she was the Theotokos, the Mother of God. There was then a Second Council of Ephesus in 449 A.D. which returned to the idea of Christ having a single nature, that of a ”divine human.”

That reversal was so upsetting to some, that they then had to have a council at Chalcedon the very next year, in 450 A.D. The council was called by Emperor Marcian, though the Pope, Pope Leo the Great, was cool to the idea of having yet another meeting, and especially one so soon after the catastrophe of the last one. The Chalcedonian council reaffirmed that Christ has two natures in one person. Christ isn’t a divine human, Christ has a full human nature and a full divine nature. They also concluded that these two natures existed “with neither division nor confusion” in one person.

This proclamation led to a major split in the church, with those in the single-nature camp (“divine person”) making up the Oriental Orthodoxy, which includes Ethiopian, Armenian, Eritrean, and Coptic (Egyptian) churches.

The error of these church leaders was their assumption that somehow the various writings they had assembled and elevated to the status of being canonical would naturally be self-consistent, and that they would thus be able to fashion a unified picture of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost.

The Reformers were equally mistaken and busily set about erecting a Systemic Theology, carefully buttressing every pillar of their edifice with references to canonical scriptures and always bending and shaping each addition to the structure to insure its consistency with the whole. The ungainly structure that resulted, however, though impressive in its breadth and bulk, (and permeated throughout with a dark and gloomy inevitability), was never very satisfying spiritually.

Christians claim to be both monotheists and trinitarians. So there has to be quite a bit of mental gymnastics and special pleading to make the concepts of trinitarianism, monotheism, and the worship of two divine beings (God and Jesus) appear to be consistent.

I expect a neutral observer of social institutions and religious practices who examined the behaviors of the practitioners of a faith would come to one set of conclusions regarding the beliefs of those practitioners (based on their actions) and another set of conclusions from the study of the creeds promulgated by their denominations.

The idea of the Trinity first appears in Christian writings about 110 A.D. (or C. E.) [Ignatius of Antioch].

Humans have always had a strong fascination with the number three and whenever a number of categories are thought to be useful in explaining a thing or phenomenon, they will frequently decide, rather arbitrarily, that the number of categories should be three, rather than two or four or some other number. Thus Freud divided the human psyche into id, ego, and superego. In philosophy we have: thesis, antithesis, synthesis. There are three Furies and Three Little Pigs. Martin Luther King wrote a speech entitled: “The Three Dimensions of a Complete Life.” There is a web page that describes what you can do when faced with an “active shooter emergency”: run, hide, fight. We congratulate or express our appreciation for people with “three cheers.” In school, we learned the “three R’s” (which was really a stretch, as only one of the words actually starts with an “r”). The circus has three rings. If you really need something, you will have to “beg, borrow, or steal,” etc., etc., etc. (Notice the three et ceteras.)

I am always skeptical when there are three categories for anything, as I find that the number of categories into which a thing can be divided is rarely inherent in the thing itself. There is no logical reason why a thing should have three and only three aspects. In the social sciences, papers so frequently appeared that divided some human experience, behavior, or social interaction into exactly three stages, that those researchers that persisted into dividing up some continuous process into three parts where called “stage-ists” and their papers derided.

In Christianity, Valentinus (~100 A.D. - ~160 A.D.) also had this natural human addiction of seeing everything as having three parts or natures, so he disseminated a work called On the Three Natures in which he claimed that the Divinity was, in some manner, threefold. His writings were later declared to be heretical.

The word “Trinity” first appears in the late second century in the writings of Theophilus of Antioch.

There was soon much controversy over what the Apostles believed. They certainly believed in a Heavenly Father, in Jesus as a savior, and in a Spirit. But in affirming that Jesus was God’s chosen one, were they saying that Jesus was a god? And not only a god, but the same God to whom Jesus prayed? In Mark 10:18, Jesus says “Why do you call me good? No one is good, except God alone.” And in John 14:28, he says, “The Father is greater than I.” In most passages of the gospels, Jesus is clearly an entity distinct and separate from God.

Yet his followers did believe Jesus was surely “divine,” and as a “divine being,” he was worthy of worship, but there is only one God. What to do?

Sabellius said that Jesus, the Father, and the Holy Spirit were all one and the same. The use of the different words merely emphasized different aspects of a single being. This idea was rejected by Rome in 220 A.D.

The distinctiveness of Jesus as a human led Paul of Samosata to say that Jesus was a human who became the Son of God when he was baptized by John. He wasn’t an aspect of a single divine being, but was instead a human who had been adopted by God. The Synods of Antioch rejected that idea in 269.

Finally, we get the Nicene Creed that says Jesus is “God of God, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the father” --- whatever that might mean.

There was then a disagreement over whether there was “one being with three essences.”

That wouldn’t do either. The bishops decided “essence” was not the correct word, there was instead “three persons, one being.” There is only one essence, not three.

The Trinity – Celtic Knot The Other 3-in-1

(As Wittgenstein showed, there is also an arbitrariness in the words we use to describe our reality and experience, which is itself a form of “categorization” but on a grander scale. The meanings of words are themselves socially negotiated.)

The “God in three persons” solution is so unsatisfying that it is not surprising that, with the Reformation, Unitarianism developed in Poland and Transylvania in 1556. By 1774 It has spread to London.

By 1786, it had reached Boston, and congregations had begun to adopt a Unitarian faith. This was a Christian theological Unitarianism and not the Unitarianism of many who make up U-U congregations today.

Religions, unlike philosophies generally, have an advantage when faced with a clash of concepts (such as monotheism and the Trinity) that are difficult to reconcile. One can just paper over the flaws by saying “It’s a mystery.”

Unless you are a rigid Calvinist, it hardly matters that a faith is not consistent or rational. Our most important experiences in life are not, after all, rational ones.

The nontrinitarian denominations today include The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (“Mormons”), Unitarian Universalists Christian Fellowship, The Church of God International, The Way International, Christian Scientists, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Christadelphians, Friends General Conference (“Quakers”), Oneness Pentecostals, and the United Church of God.

Now that Pentecost is over, we enter Ordinary Time, which is a very long time. The season after Pentecost lasts from the day after Pentecost until the day before the first Sunday of Advent. (There is another period of Ordinary Time in the church year, but we’ve already gotten through that—it was the period after Baptism of the Lord Sunday in January and lasting until Ash Wednesday.)

The introit is “Jesus, Name Above All Names.” Naida Hearn thought of the hymn and tune while she was standing at the sink doing the family laundry in Palmerston North, New Zealand, on a warm summer December day in 1974. She played piano in a Pentecostal church.

https://youtu.be/6v_7paIlK-A “Jesus, Name Above All Names,” choir anthem arrangement, sung by the Seventh Day Adventists City Choir, Adelaide

Here’s the disco version:

http://youtu.be/8_HgcQ1ktEA “Jesus, Name Above All Names,” dance version by Hypersonic

Naida Hearn thinks everyone sings her hymn incorrectly. When she wrote it, she didn’t have “Lord” in “Glorious Lord” sung on three notes, going down in steps. She wishes people would sing it the way she wrote it, with “Lord” sung on one note. But that’s never going to happen.

The opening hymn is no. 138, “Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty!”—a hymn title with two exclamation points. The words are by Reginald Heber. The tune is NICAEA by John Bacchus Dykes.

https://youtu.be/FZ_qWkaAY0A “Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty!” sung by the Altar of Praise Men’s Chorale, a cappella

https://youtu.be/FUXggCuXnCw “Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty!” sung by the group Acappella

The tune, NICAEA, takes its name from the Council of Nicaea (see discussion of the Trinity, above). Dykes wrote the music specifically for the words by Heber. Both author and composer died rather young, Heber in his forty-third year and Dykes at 52.

Reginald Heber

The author of the hymn, Reginald Heber, was born 21 April 1783 in England. He died before his 43rd birthday.

Reginald Heber was a child prodigy and was translating a Latin classic into English at the age of seven. He won two awards for poetry while at Oxford. His family was wealthy and his parents well-educated. After graduating from Oxford, he became rector of his father’s church in Hodnet, near Shrewsbury in west England.

In 1823, he was appointed Bishop of Calcutta. He did not adapt well to the hot and humid weather of Calcutta in May and June, when the temperatures often exceeds 104 °F. As Bishop of the See of Calcutta, he was required to travel long distances, going to Bengal, Bombay, Ceylon, Delhi, and Lucknow. After working in India for three years, he died of a stroke on 03 April 1826.

He wrote all of his 57 hymns before going to India. He is the author of eight hymns in our old green Presbyterian Hymnal (1933), including “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty” “Bread of the World, In Mercy Broken,” “The Son of God Goes Forth to War,” “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains.” He also wrote “O God, My Sins Are Manifold,” and “The Feeble Pulse, the Gasping Breath,” a burial hymn.

John Bacchus Dykes

John Dykes was born on 10 Mar 1823 in Hull, England. His father was a shipbuilder and banker. His mother was the daughter of a surgeon and the granddaughter of Rev. William Huntington, Vicar of Kirk Ella.

Dykes became the assistant organist at St. John’s Church in Myton, Hull, at age 10, where his paternal grandfather, Rev. Thomas Dikes, was vicar and his uncle (Thomas) was organist.

He attended college at Cambridge, where he joined the madrigal society and the Peterhouse Musical Society, for which he served as president.

After graduating, he became curate of Malton, North Yorkshire, in 1847. In January 1848 at York Minster, Dykes was ordained Deacon. In 1849, he became canon of Durham Cathedral. In 1862, he was granted the benefice of St. Oswald’s, Durham. (That is, he was to serve as vicar of the parish, and in return he was given legal possession during his lifetime of the parish’s properties and possessions, from which he was to obtain his income.)

Dykes, unlike his father and grandfather, supported the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Church of England, and supported ritualistic practices shunned by the English Reformation. He became a member of the Society of the Holy Cross and supported the use of wafers for bread and facing east when celebrating communion.

Dykes’ bishop, Bishop Charles Baring, was of the reformist wing and refused to give Rev. Dykes a curate for his parish. Dykes retained the services of the Attorney General, Dr. A. J. Stephens, QC, and took his bishop to the Court of Queen’s Bench, but lost.

Those who were in Dykes’ camp claim that the loss of the case and the resulting overwork led to his diminished health, both physically and mentally. The medical evidence suggests instead that Dykes’ loss of physical and mental health was due to tertiary syphilis. [The Life, Works and Enduring Significance of the Rev. John Bacchus Dykes, Doctoral thesis, 2016, by Graham M. Cory, Durham University, pp. 144-146.]

In March 1875, Dykes left St. Oswald’s and went to Switzerland. He then returned to the south coast of England and died in an asylum at Ticehurst on 22 Jan 1876, aged 52.

The gospel lesson is from the last five verses of the last chapter of Matthew, Matthew 28:16-20, the Great Commission.

So the eleven disciples went to Galilee to the mountain Jesus had designated. When they saw him, they worshiped him, but some doubted.

Then Jesus came up and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Therefore go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you.

And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

The epistle reading is from the last three verses of the last chapter of 2 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians 13:11-13.

Finally, brothers and sisters, rejoice, set things right, be encouraged, agree with one another, live in peace, and the God of love and peace will be with you.

Greet one another with a holy kiss. All the saints greet you.

The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all.

The second hymn is No. 132, “Come, Great God of All the Ages.” The words were written by Mary Jackson Cathey in 1987.

The tune is ABBOT’S LEIGH, 1941, by Cyril Vincent Taylor. The hymn we most frequently sing to this tune is Fred Pratt Green’s hymn “God Is Here,” No. 461. ABBOT’S LEIGH is used for many hymns, the most familiar probably being “Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken” and “Lord, You Give the Great Commission.”

There are only a few recordings of Mary Cathey’s hymn on YouTube, and they were all made in Presbyterian Churches.

You can hear the tune here:

https://youtu.be/lz6kzyhUBj4?t=39s “Come, Great God of All the Ages” (Tune: ABBOT’S LEIGH”), First Presbyterian Church, Natchez, MS

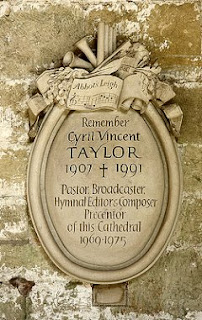

Cyril Vincent Taylor was born in Wigan, Lancaster, England, on 11 Dec 1907 and died 20 Jun 1991 at Petersfield, Hampshire, England. He was the son of an Anglican priest and attended Christ Church College, Oxford. He became the precentor of Bristol Cathedral.

During World War II, Taylor was the producer of Religious Broadcasting for the BBC, and he was stationed in Abbot’s Leigh; hence the name of the tune. In 1951, he helped produce and edit the BBC Hymn Book, which was to be used with the Daily Service broadcast by the BBC.

He was cremated at Chichester and interred at Salisbury Cathedral, Wiltshire, where his final resting place is marked by the plaque shown below, which includes the beginning notes of his famous tune:

The author, Mary Jackson Cathey (b. 1926, Florence, SC) was an elder at National Presbyterian Church, Washington, D.C. She obtained a master’s degree in 1953 from the other Union Seminary: Union Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, from which a former elder of Old South Haven also graduated.

Mary Jackson Cathey

Before going to National Presbyterian, she had been Director of Religious Education at Bethesda Presbyterian Church, Bethesda, Maryland, and before that, she held a similar position at the First Presbyterian Church of Anderson, SC. She married Dr. Henry Marc Cathey of Bethesda in 1958.

Dr. Marc Cathey, a noted horticulturist, received master’s and PhD degrees from Cornell University and worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture before becoming director of the National Arboretum (1981-1993). He is the author of the A to Z Encyclopedia of Garden Plants and many other works. After he retired in 2005, he and his wife, Mary Jackson Cathey, moved back to his home town, Davidson, NC. He died 08 Oct 2008.

The title of the sermon is “God’s Loving Face.”

The closing hymn is “Breathe on Me, Breath of God,” no. 316. ,” with words by Edwin Hatch, 1886. The words first appear in his self-published little book Beyond Doubt and Prayer, 17 pages.

Edwin Hatch was born at Derby on 04 Sep 1835.

Rev. Edwin Hatch, D.D.

Hatch was a graduate of Pembroke College, Oxford, and, at age 25, won the Ellerton Theological Essay Prize (1858). (The prize was awarded for the best English essay on “some doctrine or duty of the Christian religion, or on some of the points on which we differ from the Romish Church, or on any other subject of theology which shall be deemed meet and useful.”) He was a winner of the Stanhope Historical Essay Prize for the best essay on a subject of Modern History in 1865 (where “modern history” was defined as history of the period between 1300 A.D. and 1815 A.D.).

He served as Vice Principal of St. Mary Hall, Oxford (1867) and as Rector of Purleigh (1883). He died on 10 Nov 1889.

The tune, TRENTHAM, was not written for this hymn, but was instead composed by Robert Jackson for they hymn “O Perfect Life of Love” by Henry W. Baker.

Robert Jackson was born in May, 1842, at Royton (near Oldham), Lancashire, England. He named the tune for a village close to the town in which he was born. Jackson was trained at the Royal Academy of Music, then was the organist at St. Mark’s Church, Grosvenor Square, London, but only for a short time.

Most of his life he was the organist at St. Peter’s Church, Oldham (1868-1914). His father preceded him there as organist, a position that his father had held for forty-eight years. Robert Jackson held the same post as his father for forty-six years. So, together, they were the organists at St. Peter’s, Oldham, for nearly a century. Jackson died 12 Jul 1914 at Oldham.

The Psalter Hymnal Handbook says that this “serviceable tune” is “barely adequate for the fervor” of the text of “Breathe on Me, Breath of God.”

https://youtu.be/M5keJHZdWYM “Breathe on Me, Breath of God,” the Mountain Anthems, a cappella

Instrumental Music

The prelude is a melody from Christoph Gluck’s ballet Alessandro (Les amours d’Alexandre et de Roxane) which premiered in Vienna on 04 Oct 1764. Gluck composed the music for eight ballets and 49 operas (35 are full-length operas).

You can hear Alessandro (The Loves of Alexander and Roxane) here:

https://youtu.be/GHW-ws_rhKk The music of Christoph Gluck’s Alessandro

Christoph Willibald Gluck was born 02 Jul 1714 in a region of Germany then called the Upper Palatinate (near Neumarkt in Bavaria). He grew up in Bohemia, then, according to some, went to Prague, where he studied logic and mathematics in 1731. In 1737, Gluck went to Milan where G. B. Sammartini was his teacher. He composed his first opera there in 1741.

In 1745, he went to London where the composed two operas and became acquainted with the music of Handel. Handel himself was somewhat critical of Gluck’s music. Handel said his cook knew more about counterpoint than did Gluck. However, Handel’s cook was Gustavus Waltz who sang in some of Handel’s productions and was an excellent contrapuntist.

After London, Gluck traveled to Dresden, Vienna, Copenhagen, Prague, and Naples, finally settling in Vienna in 1754. In Vienna, Gluck mentored Antonio Salieri.

Gluck brought a new style of opera to the Hapsburg court there, which, for the period (the 1760s), was called “radical.”

In Paris, his patron was Marie Antoinette, one of his former students who, in 1770, had married the future king of France (King Louis XVI). While in Paris, he merged the styles of French and Italian opera. His greatest success was the opera Iphigénie en Tauride.

In 1779, Gluck suffered a stroke and returned to Vienna. He recovered and continued to produce new works, though none were major. On 15 Nov 1787, he had another stroke and died, age 73.

The music for the offertory is “Ave Verum” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

This music will be familiar to the choir because we’ve sung it (or, at least, practiced it).

In the Middle Ages, “Ave verum Corpus” was sung at the elevation of the host during consecration—a practice strongly denounced by the English reformers in 1549. (Martin Luther retained the elevation of host, but in England, it was forbidden.)

Queen Mary I, (known as bloody Mary for the many Protestant leaders she had burned at the stake), reinstituted the Catholic mass.

Her half-sister, Queen Elizabeth I, brought back Protestantism and again banned the elevation of the host.

[Queen Elizabeth I also held to another policy of the Reformers, the prohibition of the use of candles when none were needed. At the opening of Parliament, when Elizabeth was met by monks with candles she unceremoniously dismissed them, “Away with those torches; we can see well enough!”]

In the English Reformation, the Puritans in particular believed that the church had been corrupted by the adoption of superstitious practices meant to dazzle the worshippers rather than lead them to a true understanding of how to lead a Christian life. They totally rejected the doctrine of transubstantiation. It is from them that we get the word “hocus pocus.”

According to the Oxford English Dictionary,

"hocus pocus", the traditional magician's incantation derives from a distortion of hoc est enim corpus meum - "this is my body" - the Latin words of consecration accompanying the elevation of the host at Eucharist, the point, at which according to traditional Catholic practice, transubstantiation takes place, which was mocked by Puritans and others as a form of "magic words."

You can hear this piece sung here by the boys’ choir, King’s College.

http://youtu.be/HXjn6srhAlY King’s College Choir sings “Ave Verum Corpus (Hail, true Body)” by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

or you can listen to The Concordia Choir sing it here:

http://youtu.be/1Qxrru15jfo “Ave Verum Corpus” sung by The Concordia Choir of Moorhead, Minnesota

The postlude is “March in C” by Carl Maria von Weber.

https://youtu.be/vudJpIPDJHI “March in C” by Carl Maria von Weber

Carl Maria von Weber, 1820, six years before his death

Carl Maria Friedrich Ernst von Weber was born 18 Nov 1786 in Eutin, Bishopric of Lübeck, Germany. His mother was a singer. His father was a violinist.

Carl’s father, Franz, inserted “von” in his name to make it sound more aristocratic.

Carl Weber had a musical education. At age 12, in 1798, he studied with the younger brother of Joseph Haydn, Michael, in Salzburg. That same year, he also studied with the singer Walllishauser in Munich, and with the organist Johann Kalcher. He published his first works that year, six fughettas for piano. He soon composed his first opera, a mass, and Variations for the Pianoforte.

At age 14, he wrote another opera, The Silent Forest Maiden, which was performed in the Freiberg theater. (It wasn’t a success.)

At age 17, he wrote the opera Peter Schmoll and his Neighbors which was produced in Augsburg and was more favorably received.

When he was 18, he became Director of the Breslau Opera. He tried to pension off the older singers and have the company perform more challenging works, but this proved unpopular—both with the musicians and with the public.

From age 21 to 24, he was the private secretary of Duke Ludwig, the brother of the king of Württemberg, King Frederick I.

Things did not go well with Carl von Weber during this period. His father embezzled a great deal of the Duke’s money, and Carl had an affair with an opera singer, Margarethe Lang, that ended badly. Carl and his father were banished from the kingdom.

After that, he was Director of the Opera in Prague (1813-1816) and Director of the Opera in Dresden (after 1817), while continuing to compose music himself.

He married the singer Caroline Brandt on 04 Nov 1817.

In 1824, he was invited to compose and produce a work for the Royal Opera, London, which he did, conducting the premiere on 12 Apr 1826. He had contracted tuberculosis before arriving in London, but continued to conduct twelve more performances, all of which were sold out. He died in London on 05 Jun 1826 at the home of Sir George Smart, where he had been staying. He was 39 years old.

Richard

No comments:

Post a Comment